Primary schools increasingly expensive due to increasing parental contribution

The amount that primary schools ask for parental contributions has increased by more than 20 percent in five years, according to the Education Inspectorate. There are also more frequent excesses: primary schools that charge 1000 euros or more. The Education Magazine spoke three.

Image: Angeliek de Jonge

Another topic that shows that inequality of opportunity is increasing, according to the AOb. The inspectorate does not say how many primary schools charge more than 1000 euros. She does explain that it is a difficult matter. Apart from the official voluntary parental contribution, other amounts of money are often asked from parents throughout the year. And not every board includes parental contributions as an official item in the annual accounts, making it difficult to gain insight into how high the costs for parents actually are.

Differences by region

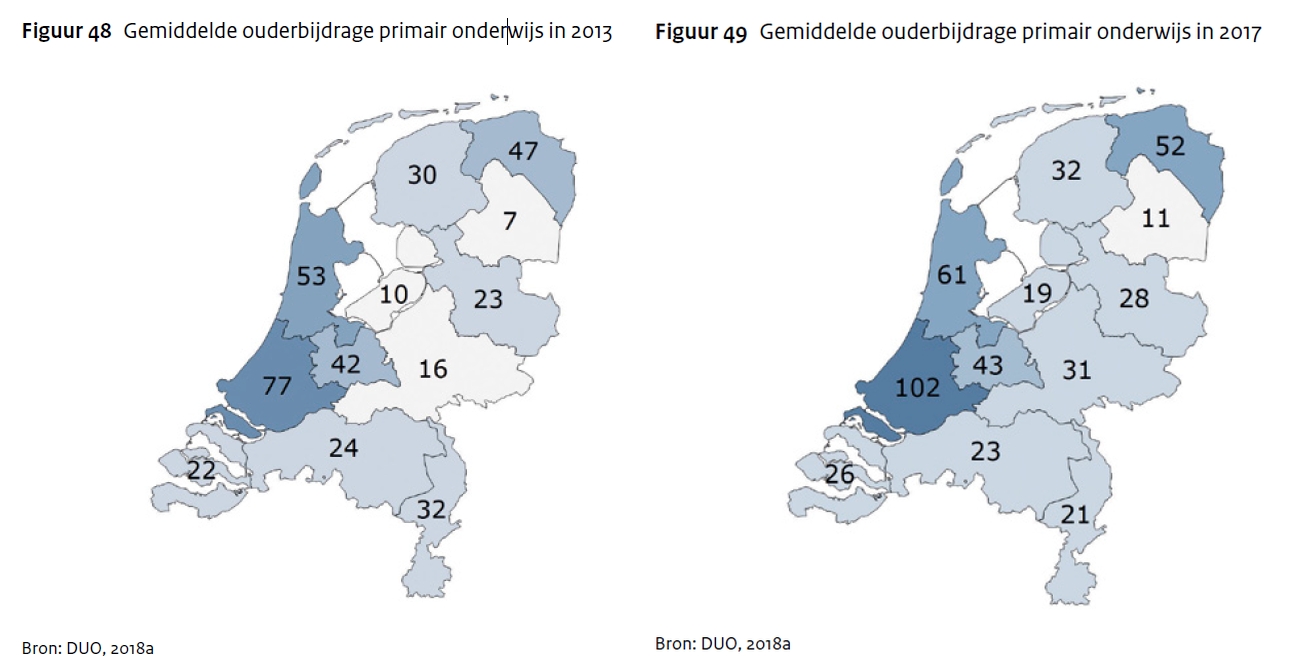

The Education Inspectorate looked at the annual accounts of school boards in primary education and encountered parental contributions by 62 percent of school boards. The regional differences are large: primary schools in Drenthe charged an average of only 2013 euros per child in 7, compared to 2017 euros in 11. In 2013, 77 euros on average was requested in South Holland. In 2017 that is 102 euros on average per child. On average, the parental contribution has increased from 41 to 50 euros in five years, an increase of 22 percent.

Excessively high

The primary schools that charge exorbitantly high parental contributions are striking, editor Robert Sikkes also points out in the Education Magazine. More than 1000 euros per year is no longer an exception. Three of these schools explain in the December issue of the Education Magazine why they do this and where the money is going. They do not spend these extra euros on things that fall outside the curriculum, such as celebrations and school trips, but on smaller classes, other teaching materials or a wider teaching environment. As a background: a school that receives more than 1000 euros per child per year, easily has 20 percent more budget than other primary schools.

The Casaschool asks for its basic package - the school also offers extensive childcare options –1045 euros per year. Director Tessa Wessels prefers to say 87 euros per month. “Parents must both have work, but that could also be at the Albert Hein. If it is important to you, you can afford it. ”

Cut back

The Kievietschool in Wassenaar - parental contribution: 1425 euros per year - writes in its school guide, for example, 'In recent years, the government has cut back tremendously on education. As a result, almost all primary schools in our country have between thirty and forty children in a class. The aim is a group size of 25 (…) students. ' In Pijnacker, the Casaschool provides bilingual Montessori education. The teaching materials for English, the bilingual library and the daily meals at school are paid from the parental contribution of EUR 1045.

From the age of six, the children at the Casaschool help themselves to cook.

Did not work out

According to Lisa Westerveld, Member of Parliament for GroenLinks, substantial parental contributions are yet another example that the basic funding of schools is not sufficient. “Up to now it has not been possible to raise that amount. There is no majority for that in the House of Representatives. ” Rudmer Heerema is education spokesperson for the VVD and does not find it a problem that parents who have more money to spend can choose schools that ask for a higher parental contribution. He does not see the link with a growing inequality of opportunity. "That's more how other political parties frame this topic."

Heerema does find it distressing when a high parental contribution leads to exclusion. Examples of this were regularly in the media last year. Stories of teenagers who are not allowed to travel abroad, or students whose parents cannot afford the iPad and who are put behind a PC in the back of the classroom.

Bill

Westerveld of GroenLinks, together with Peter Kwint of the SP, is preparing a bill that states that children should not be excluded from school activities because the parental contribution has not been paid. The proposal does not limit the amount of the parental contribution, which means that the AOb would like to. A conscious choice, Westerveld explains. “If you want to get a bill through the House of Representatives, you shouldn't want to change too much at once. For us, preventing children from being excluded was now a priority. ”

Whenever the parental contribution is politically under discussion, and that happens every term of office, the outcome of the debate is: the sector must arrange this itself. The PO Council, an association of school boards in primary education, just like the VO Council, agreed a guideline with the boards at the end of November. The PO Council states that the parental contribution is 'voluntary at all times', that pupils may never be excluded if parents do not pay the contribution and that the school board must determine the amount 'in fairness and reasonableness'. PO Council chairman Rinda den Besten: "This is an important first step that we take very seriously."

When asked, chairman Den Besten indicated that she cannot impose sanctions if boards do not comply with the guideline: “We are not a police. Some of our supporters demand high parental contributions and they find this a very difficult subject. " Hence the attempt by Westerveld and Kwint to regulate the prevention of exclusion by law. “Then the inspectorate can enforce this,” says Westerveld.

On January 15 there will be 'written consultation' in the Lower House about the findings The financial state of education 2017, where research into parental contributions has also been given a place.

From the Education Journal

- Read the here analysis by Onderwijsblad editor-in-chief Robert Sikkes about increasing parental contributions in primary education.

- Click on the link for a look behind the scenes three primary schools offering more than 1000 euros per year.